My previous post ‘slow scholarship starts with slow reading’ prompted some questions around slow reading. What do I really mean by slow reading, and how do we do it? It is, I acknowledge, much more than not being distracted.

Although I blog, am an avid user of evernote, use Goodreads, and keep all my references in endnote (now) or zotero (in previous jobs), I have to admit that my slow reading is very visceral, material and old-fashioned. I still far prefer solid print books, and although I love the convenience of accessing my notes on evernote, the embodied act of writing out quotes and thoughts in a real paper journal with an actual pen is, I have to admit, much more conducive to savouring and enjoying and absorbing the content of a book. I also far prefer books to journal articles, because the authors have often distilled and reworked their content of years into a slower, fuller piece of work. So how, then, in this digital age, do I manage to cultivate a practice of slow reading?

1. Choose a book

If you are serious about slow scholarship, it seems a kind of no-brainer to go with books. While it can seem like forever getting your journal article published, in reality, it is rarely more than a year, and it rarely takes more than a year to write. (Although I’m currently in my fifth year of an article — maybe it needs to be a book?) I think books normally take around ten years from start to finish, including research. I think writers have time to consider the best theory for their empirical research (if included) and resist fads. They may have also developed many of their ideas in articles, and packaged them together into a larger project in a book. So for slow reading and slow scholarship, I opt for books. Monographs, not edited collections. To be really honest, I really only deeply engage with two or three academic books a year. It is really important, then, to pick books that are going to really push my own scholarship forward.

How do you know what to choose? I’m not sure I yet have the best answer to this question, except that I am partly informed by the work of colleagues I respect and admire, and the push of reading groups. Currently I am reading Jane Bennett’s Vibrant Matter: a political ecology of things, mostly because I was co-authoring a chapter on feminist political ecology and my co-authors suggested it as an important theoretical foundation not to feminist political ecology necessarily, but as a way of connecting our own work in to the discussion. But this year, I also read Miranda Joseph’s Debt to Society, because I was invited to write a book review for a symposium, and it was on a topic I was interested in and published by University of Minnesota Press, with whom I had just signed a contract. I have, of course, read other books this year, but these are the ones I have done my slow scholarship routine on. So to choose then? The following are my main considerations:

- Recommendations and reading groups

- Invited responses

- Important in the field

- Always with theoretical oomph

- Well-written

It’s hard to tell if #5 is going to hold (or #4 for that matter) — but I deeply engage with the preface or introduction to get a sense of the author’s writing style. It is pretty important if its going to be one of my ‘it’ books for the year, but if it fits the other 4 considerations, and I have the energy, I might read a less clear and stylish book through.

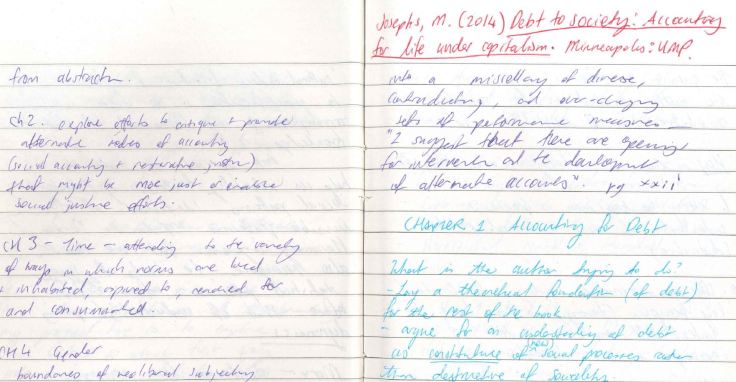

2. Start a notebook

I like to keep a hardcover, A5 lined notebook with whatever book I am reading. This is a habit I started at ANU while doing my PhD, because our department provided these in the stationery cupboard! Most books are more like A5 size, so this works well. I like a nice pen too, easy to write with, an ink pen rather than a ball point. I’m currently using a uniball eye micro roller pen. What I am doing here is trying to harness the pleasures of reading and writing, to make the task something I look forward to and enjoy, with special tools of the trade.

I head up the first page with a full reference. Nothing worse than coming back to your notebook, having returned your book to the library, and NOT having the reference details to hand. Although, really, it’s now 2016 and we can find it on the internet. But old habits die hard. There is something meditative about the writing out of the reference, focusing on my handwriting and the pleasure of the pen and paper.

3. Two kinds of notes

Initially, I make two kinds of notes, and I separate them with a line drawn across the page when I transition between. These are 1) quotes and 2) reflections. Most of the time, I actually copy out quotes. CRAZY, I know. But again, I find there is something meditative that comes with copying out a quote, in full, by hand (don’t forget page number). I reflect on each word and the choice of each word as I copy, and because I am copying by hand, I only copy out something really good.

When I get a feeling like I’m going to explode if I don’t write something down, I draw a line across the page and write a reflection or thought. You may be surprised to know that for me, this is often theological — or ontological, really. As I read and write out quotes, I am thinking, ‘if this is true, what does it mean for the nature of reality? And what does that mean for my faith and understanding of the world?’. Sometimes this is a moment of critique, but for the most part, I try to hold back on critique until I have the full picture. It’s more like a chance to think through the consequences of what the author is saying. An example, from Jane Bennett:

What I am calling impersonal affect or material vibrancy is not a spiritual supplement or ‘life force’ added to the matter said to house it. Mine is not vitalism in the traditional sense; I equate affect with materiality, rather than posit a separate life force that can enter and animate a physical body.

My aim, again is to theorise a vitality intrinsic to materiality as such, and to detach materiality from the figures of passive, mechanistic, or divinely infused substance. This vibrant matter is not the raw material for the creative activity of humans or God. (2010: xiii.)

Then a line, then my thoughts:

What would this mean for my theology? For me, this does not undermine the reality of the spiritual realm, the spirit of God, in fact, it seems clear to me that God is capable of — and would delight in — coaxing and cultivating agentic matter as much as manipulating raw material. The former is perhaps more in the character of God than the latter. It would be interesting to re-read the bible with an eye to materialism — for example, the stubborn materiality of the old testament! Thinking of Adam’s naming and knowing of plants and animals (which implies conversation or at least relationship with) stones shouting out, trees clapping, for example, and the implied materiality of Hades and Abraham’s bosom. Also the resurrection….

Granted, my thoughts aren’t very coherent and please don’t hold them up as necessarily what my final thoughts on Bennett’s work will be. (And, not the place to try and critique my theology here either, guys). I am trying to provide an example of reading with an open stance, a ‘what if’, responsive approach to reading, and the kinds of notes this produces.

4. End of chapter processing

At the end of each chapter, I put my thinking hat on and use the following questions as guidelines for summary and critique. These questions loosely come from The Student’s Writing Guide for the Arts and Social Sciences, by Gordon Taylor – 1989! My PhD supervisor Katherine Gibson gave me and my colleagues a photocopy of Chapter 3 Reading and Taking Notes when we first started. But she summarised it into these four questions (which my own students will recognise now):

What is the author doing? Is the author exhorting, arguing, explaining, describing, conceding … and why? What is the motivation for this? I like to write this in one full sentence.

How is the author doing it? What kinds of evidence, modes of analysis, and structure are they using to achieve their goal? Are they comparing, defining, observing, evaluating…? In what parts or steps are they doing this, and how do these parts relate to each other? Again, a full sentence or two rather than notes here.

How does this relate to other things I’ve read? Can I put the author in historical context, or their theoretical lineage? Does it contradict or support work in other lineages, or other things I have read? Here I might write a bit more, and a bit more in note form if I need to cover a lot of ground. But it still helps to have a sentence or two in coherent English (or whatever language you take notes in) for use in future writing.

What do I think? We come to this last, because we cannot truly critique until we have understood. I normally try to write 3-4 sentences here, with particular reference to projects I am working on.

All up this end of chapter processing is about 1-2 pages of my A5 notebook, and it is GOLD. I can’t remember what a book or chapter is about from one day to the next, but this has my fresh PROCESSED thoughts ready for use in writing.

5. Repeat until done. Then, end of book processing.

I use the same four questions to reflect on the book overall. What you may have gathered here is that I now have the basic outline of a solid book review. One would think I had published more book reviews, given I do this for a few books a year. But in reality, I rarely have the happy circumstances meet where there is a book I want to read that is recent enough to warrant publishing a review. But if you want to see some examples, try these two reviews cited below, built on this approach of constructive/appreciative critique. Both were commissioned, and neither were books I would have picked up necessarily – but others recommended me as reviewer and I thought they must see me and my interests in the book somehow, so I gave it a go.

Even if you don’t publish a review, you probably have a good set of notes, quotes, and a few fully processed thoughts to use in your work. Maybe only one sentence on the book will make its way into your finished piece, but it will be solid. In actuality, I find a book that is deeply engaged with seeps into your work in unpredictable ways, and may start to be a supporting pillar or touchstone in your intellectual work. Liu Xin’s work certainly did that for me while writing my PhD.

Finally, Cultivate Enjoyment

Reading can be a chore, especially if you are literally a slow reader (I am a relatively fast reader, so I have to cultivate slow reading, metaphorically…). One thing I’ve learned in this job is to cultivate enjoyment in necessary tasks. While I’ve yet to manage that for email (good beats on spotify help though), I do believe I’ve managed this for reading.

I’ve mentioned the pleasure of the print book, the notebook, and the nice pen. I also try to cultivate other little rituals around reading. Currently, I have a comfortable chair in my office and a nicely proportioned and decorated space with a few nice objects I love, with colours I like. For reading, I leave my computer, make a cup of tea, sit in the chair with my feet up and shoes off, sometimes with a blanket (!) and allow myself the luxury of uninterrupted, slow reading for an hour. It has to be in the morning, or I fall asleep.

When I did not have such a comfortable office, I used to make a time every afternoon to leave my office with book, notebook and pen, and sit in the Massey University Staff Club with a cup of coffee (they used to put a tiny piece of fudge on the side for free) and cultivate the pleasure of the wonderful garden out the bay windows (or actually be in it, on a nice day). In other workplaces, I have found cafes or outdoor spots nearby, and connected reading with some other pleasure — the outdoors, coffee, food, time away from the desk and screen. Connecting reading with pleasure relaxes the mind, and stills the panic of producing stuff, allowing you to absorb and understand and process what is going on in the head of another.

Well, there you have it folks, your very own how to on slow reading! I’d love to hear your thoughts and if others have useful tips, please share them below in the comments.

UPDATES: Q1: Do you read journal articles in the same way? Sort of, I don’t take extensive notes or write out quotes, but I read them in print or onscreen, then I tend to answer my four questions in an Evernote note with the pdf attached. Q2: What do you do with all the old notebooks? I keep them on my top shelf and refer back to them every so often. I number the pages and write an index in the front with the authors name and book, plus the page in the notebook I can find it. But I have also scanned most of them into Evernote, which has handwriting recognition and is searchable. I’m actually only on my 4th notebook in 10 years, so it’s not a biggie really.

Awesome post Kelly. I was just uploading the Spew draft piece, and noticed this. I am in awe of your discipline. I follow the same process for marking PhDs, but with a great book like ‘seeing like a state’, I find I am so enamoured of the material and writing that I end up reading it a fiction thriller; a month later very little of the arguments remain lodged in my head. i must try this approach.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am exactly the same Lindsey! I remember the feeling of loving it but can’t remember why. Hence trying to be disciplined with at least a few books a year.

LikeLike

This is so affirming for me 🙂 I read slowly and make notes, but journaling the thoughts into a nice book to go back to (and indexing!) is such a great idea.

LikeLike

Thanks Megan, I have just been deliberately slowing down and reading and prepping as I rewrite an article with colleague. We had such a productive day, because we made time for reading and discussing before the writing started. No pretty notebooks this time, but the skills of slow reading seem to be becoming more engrained in me!

LikeLike

I sometimes find it so hard to read slowly as it doesn’t feel productive (especially if I’m a hurry to get something written). But unless you have done those (hard?) yards, the writing just…won’t…come. So forcing yourself to slow down is worth it.

LikeLike

I think you are right. On the other hand, the last few weeks I’ve been trying to read while walking(!) to work, which encourages me to just keep reading even if I’m unsure. Something about the physical activity and reading while walking seems to help me absorb the main ideas of a piece without feeling I have to produce. I guess it’s still slow reading, but less attentive than the journal method.

LikeLike